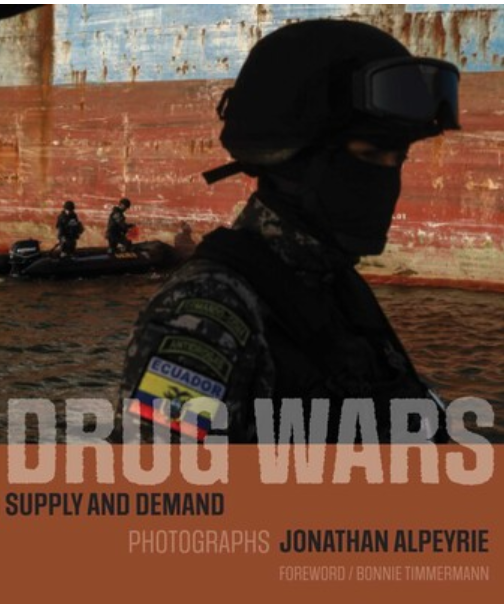

Drug Wars by Jonathan Alpeyrie

In this interview with Cinzia D’Ambrosi, founder and director of the Photojournalism Hub, photojournalist Jonathan Alpeyrie reflects on his years documenting some of the world’s most dangerous conflicts and his latest investigation into the drug wars. Known for his immersive, on-the-ground approach and his ability to reveal the human stories behind global struggles, Alpeyrie discusses why he felt compelled to take on one of the most dangerous and underreported subjects in contemporary journalism. The interview offers a rare insight into the risks and deep commitment that underpin Alpeyrie’s work as he brings visibility to stories often hidden from the public eye.

The drug trade is a notoriously difficult and dangerous subject to cover, with limited access and huge personal risk. What drew you to this topic, and why did you feel it was important to take on, despite the danger?

The drug trade is an incredibly difficult and dangerous subject to cover — access is limited, the environment is unpredictable, and the personal risks are significant — but I felt compelled to take it on. What drew me to this topic was the hidden human cost behind the headlines: the communities trapped between cartels and law enforcement, the young men pushed into cycles of violence, and the corruption that quietly shapes daily life. Having spent much of my career documenting conflict, I saw the drug war as a global struggle that is often misunderstood or overlooked, yet profoundly consequential. Despite the danger, I believed it was essential to capture these realities from the ground, to show people what this conflict truly looks like and how deeply it affects those who live within it.

It is also not a subject that is widely published or visually documented, at least not at this level of intimacy. Did that sense of underexposure influence your decision to pursue it?

the lack of visual documentation was a major factor in my decision to pursue this project. For a conflict as far-reaching and destructive as the drug war, I’ve always been struck by how little intimate, on-the-ground imagery exists. Most coverage stays at the surface, focusing on sensational moments rather than the human reality beneath them. That sense of underexposure pushed me to go deeper, to gain access to places and people rarely seen, and to document the everyday rhythms of a war that is often invisible to the outside world. I felt there was a gap that needed to be filled — not for shock value, but to give context, nuance, and humanity to a subject that affects millions yet remains largely hidden.

Your career has taken you into war zones and conflict areas around the world, including your experience of captivity during the Syrian Civil War. What drives you to choose these extremely challenging, often high-risk stories?

What drives me toward extremely challenging and high-risk stories is a combination of curiosity, responsibility, and a belief that certain realities demand to be documented, no matter the difficulty. Throughout my career — whether covering conventional wars or navigating the criminal conflicts of the drug trade — I’ve been drawn to places where the human experience is laid bare. My captivity in Syria only deepened that conviction. It reminded me how fragile life is, but also how important it is to shed light on the people living through these circumstances every day, without the option to leave. I choose these stories because they matter, because they shape the world in ways most people never see, and because I feel a duty to bring those unseen truths to the forefront with honesty and respect.

Do you see a thread that connects your past conflict coverage with this investigation into the drug wars? Is there a continuity in the types of human conflict you are drawn to document?

You are known for deeply immersing yourself in the environments you photograph. What role does immersion play in your work, and how does it shape the stories you can tell?

Yes, there is absolutely a thread connecting my past conflict coverage with my work on the drug wars. Whether I’m documenting a front line in a conventional war or following law-enforcement units and criminal groups in the midst of the drug trade, I’m ultimately drawn to the same fundamental human dynamics: power, fear, survival, and the way ordinary people are caught in forces far bigger than themselves. The drug war may not look like a traditional battlefield, but its impact is just as devastating and its structures of violence are just as complex. For me, the continuity lies in exploring how societies fracture under pressure, how individuals navigate danger, and how these conflicts shape communities in lasting ways. The settings change, but the human stories — the ones that reveal resilience, suffering, and moral ambiguity — are what consistently pull me in.

To capture what you did for this book, you clearly needed extraordinary levels of access. How did you build trust, navigate hostile environments, and gain proximity to people and places that are usually closed off to outsiders?

Gaining the level of access required for this book was a slow, deliberate process built on trust, patience, and a deep respect for the people allowing me into their world. I’ve spent more than two decades working in hostile environments, and over time I’ve learned that the only real currency in these situations is credibility. I approach everyone — whether law-enforcement officers, community members, or individuals connected to the drug trade — with honesty about who I am, what I’m doing, and why I’m there. I never rush access, and I never pretend to understand their reality better than they do. Bit by bit, that openness creates space for genuine relationships.

Navigating dangerous environments requires vigilance, humility, and a willingness to disappear into the background when necessary. I make myself unobtrusive, follow local rhythms, and rely heavily on the trust of people who know the terrain far better than I ever could. In many cases, it was the respect I showed for their work and their risks that allowed me to get close to situations normally closed off to outsiders. Ultimately, the access came from demonstrating that I was there to observe truthfully and responsibly — not to sensationalize, but to document a world most people never see.

Was there a particular encounter or story from this project that stayed with you?

One encounter that has stayed with me was a long night spent with a small group of local residents who lived directly between rival criminal factions. They weren’t police, traffickers, or soldiers — just ordinary people trying to survive in the middle of a conflict that had nothing to do with them. Listening to them talk about their routines, their fears, and the small strategies they used to keep their families safe was incredibly powerful. It reminded me that behind every headline or statistic, there are real lives shaped by forces they can’t control. That night underscored why I took on this project in the first place: to show that the drug war isn’t an abstract issue, but a daily reality for countless people whose stories rarely make it into the public eye. That human element stayed with me long after I left.

Jonathan Alpeyrie

www.jonathanalpeyrie.com

@jonalpeyrie

To purchase a copy: Drugs and Wars

Publishers: Simon & Schuster